Volume 2: Hunger

As the year begins, this volume turns its gaze inward, exploring the delicate ways we come to know ourselves not only through self-exploration but also through our connections with others. Sometimes, it is shaped by the people who surround us, their presence revealing parts of ourselves we didn’t know existed. Other times, it is deeply personal, a quiet exploration of our own desires, rituals, and reflections. Together, these pieces remind us that self-discovery is a patchwork—formed in moments of solitude and in the spaces where our lives intersect with others, always evolving, always unfolding.

With a new year comes the promise of possibility—a moment to pause, reflect, and rediscover. In this second volume of Between Magazine, we invite you to step into these stories and artworks as a mirror to your own journey. Let these pieces guide you through the delicate interplay of connection and solitude.

Ashmia Yasmin | Substack | Instagram

The smell of uunsi on a Saturday morning is like a hug— or a slap—depending on the memory. Every Saturday morning, the house was cleaned from top to bottom. My mother stood over the rest of us, supervising, as corners were scrubbed. The walls, a faded white that hardly required scrubbing, had to endure the harsh mop my Auntie wielded. As the youngest, my main duty was not to ruin all the hard work. I was not to touch anything. I was not to disturb the equilibrium of this newly pristine house. Every Saturday like clockwork the house was renewed.

After uunsi was lit, the fragrance would wash over the house and I knew what to expect next. My mother would go shower. Her second or third of the day. She would oil her skin, and pull out a dirac never worn before. Baati’s were every day. Common. The dirac was symbolic. Of joy and celebration. A good day. She would tie shash around her head, tuck the dirac in her

gorgorad and throw a garbasaar on her shoulder. Gold jewellery was on and the clang of bangles was her signature sound. Shakir Essa and Abdilkadir Jubba would be playing on the television.

I would watch with fascination as she came together.

It was ritualistic. The act of self-care.

The Saturdays of my childhood. It was the one day of the week when my mother became more.

She would create this space for herself, both physically and emotionally. As the house became cleansed, she, too, was changed. It was Pavlovian— the steps before are vital for her stepping into herself.

I did not understand what I was witnessing but knew it was important.

You could ask for anything and in that moment the world was open to you. A personal wishing well. She would fondly hold me while singing Somali songs to me. In those moments, I wished to understand my tongue. She cradled my head against her belly and I gazed up at her, desperately trying to bottle the moment.

Even now, I can smell the incense from memory. A love-hate relationship. I wear baati’s and tie shash on my head. I’m obsessed with beautiful diracs and I cannot wait to own at least ten of them.

I have my rituals. The things I do to step into myself.

Now and then, I think of the Saturdays before. Those that shaped me, those I did not pay attention to and those special ones. The ones where everything is okay. I have also undergone my evolution. I have met versions of me and buried them. I have similar anchors of my own. I oil myself like I watched her do it, and I now listen to Somali music. I stumble on the words of my tongue trying to mimic what I had seen others do— foreign and familiar— trying to connect to something I never knew—not fully. How do you claim that which you had a passing acquaintance with?

I think of her closed eyes, quietly humming a tune, lost in her own world. She looked content—like happiness had finally found her.

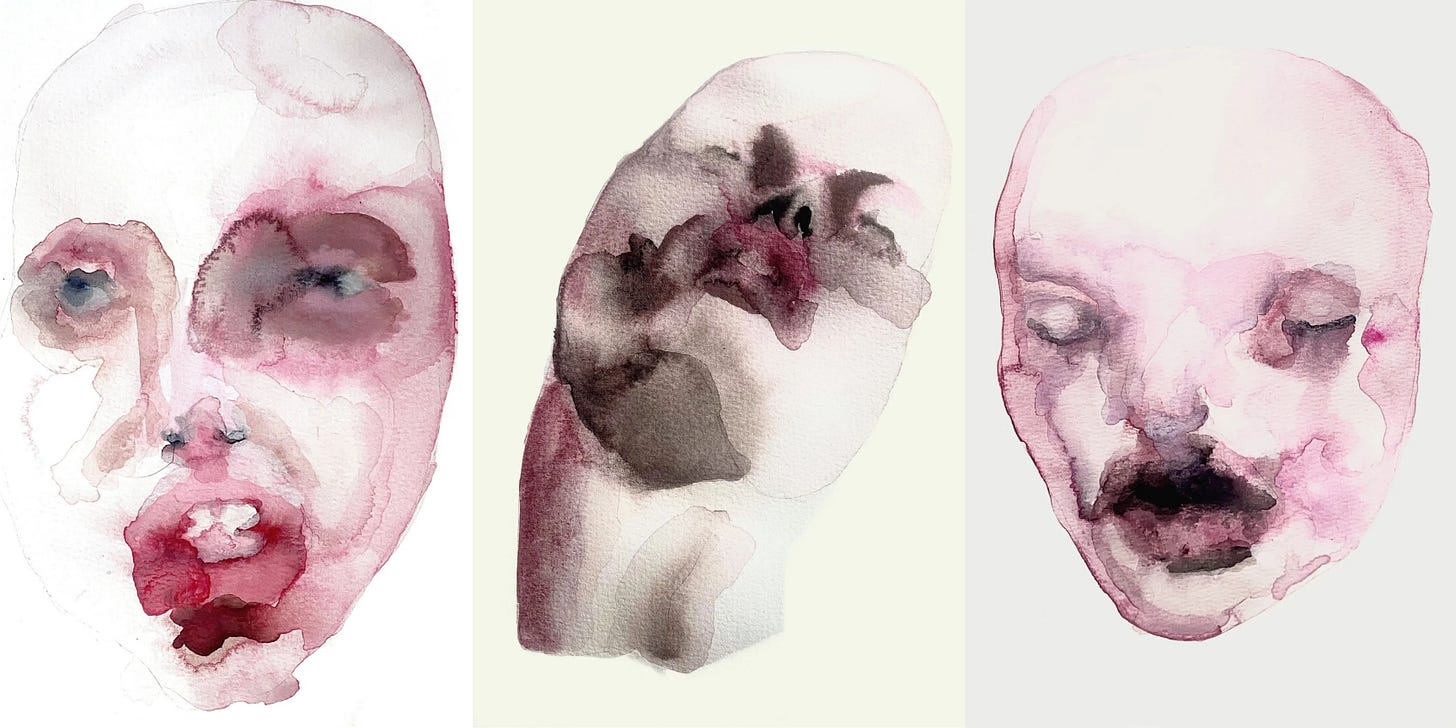

s.j | Substack | More from her

S.J. has been in love with art most of her life. She started tapping into her admiration for art more seriously in 2022. S.J. has tried different media from graphite to acrylic paint, but she instantly fell in love with watercolor. Using watercolor as the basis of her portrait work helped her put a face to the expressions in her mind. Her watercolor portraits are a visual representation of her struggles with her disorders and just a peek of what it’s like to be in her world.

MNA-mattersnotart | Instagram

I love art. Whether it’s illustrations or posters or videos. I love to make it and convey a feeling or share something I’ve been interested in, sometimes without the need for words.

This video was just that.

I wanted to capture how it felt to go out and explore the neighborhood at night with a dear friend, the silence, the noise, the environment, and myself. No fancy tools or a great purpose, just the desire to feel, create, and learn.

Hunger

Wilhelmina Asaam| Substack| Instagram

Since plastic bags became illegal, I’ve found a million ways to store my groceries. Shirt pockets. Under my arms. Thrown over my shoulders. Anything to avoid paying for one of those flimsy paper bags.

They’re so thin, you walk too long and the straps snap or the heavy items fall straight through the bottom like they’re trying to escape. I get it.

And that day I’d been on my way home, head down as usual, when a jar of organic borlotti beans appeared at my feet … and then another – which I followed to a pile of groceries on the street. I picked them up, and stuffed them in my pockets, under my arms. Then I noticed a tomato, bursting juice from its fragile, torn flesh, yet still mostly intact. I picked it up, held it up, and saw the tiny pieces of gravel embedded in it.

I guess they noticed me then, when I held it up.

He grabbed my hand first and I wondered how he knew. How he looked at me and knew I wouldn’t yank my hand back, rough him up for thinking me that way. It wouldn’t be how I dressed, I was ostensibly masc in a plain white T-shirt and dark-wash jeans. But he looked at me and he just knew.

When I was younger, boys used to educate me all the time and that’s when I knew I liked them just as much as I liked girls. While girls heard me, gave me voice, with boys I was rendered mute, my opinions sucked inwards. I’m not sure I can blame them. I’d just nod. Because I’d heard they liked your silence. I saw girls do the same to me, how it made me feel important. I’d stand there, looking at their lips curled up one side, the gorgeous arrogance, the faint smudge of moustache hair sprouting, mirroring my own budding adolescence, and I’d just nod and nod and nod as they spouted half-truths, not bothering to look for something else between.

Things I’d never say out loud:

Yeah yeah yeah, just kiss me.

Your age shows in that little slip of skin under your bum that sags.

I hate it when you fight.

I’m scared of what’ll happen when you die first.

People always assume it’s kinky because we’re three. Or perhaps the things we do together to strike pleasure are kinky because our setup is unconventional. But what is kink if not the most unadorned versions of our desires?

She kisses me first, removes my clothes, makes me feel safe and straight, whilst he watches. Then once I’m ready, sedated and made docile by my vulnerability and desire, he makes his way over. Languid, serpent-like, clothes shedding with every step until he meets me the same way. And by then, I take everything he gives me.

I’ve always taken it. Whatever I’m given.

I nodded kindly, reassuringly, wrapped my arms around a girl I loved when she cried about her ex. ‘I can’t believe he would do something like that to me.’ Mind you, the act in question was that he’d posted a photo with a new woman. Even if it was moments after we’d just declared our like and intent for each other, I just took it.

When I’m told how useless I am, when tasks are wrenched from my capable fingers; my aptitude viewed as a chaotic storm to the ship’s path. Other’s abilities – anyone else’s – seen as the stillest water. I just take it.

I stifle and push myself down. The self inside that wants to say, shut the hell up, I know what I’m doing and your advice, even well-meaning is demeaning. But I just take it.

‘Here, take this.’ His hand was outstretched with a stack of notes.

I was insulted at first, did they think I was for sale?

‘I don’t mean it like that. It’s just, we see how you struggle and you shouldn’t have to.’

I never asked. Never even thought they noticed the funny ticking sound my car made when I brought it to a stop outside their townhouse. Or how I insisted on only drinks when we met up, determined to hold my own. Or the way my phone pinged on days off with relentless messages from my impatient boss. It’s funny how the least skilled jobs seemed to demand the most of your time.

‘You’re too pretty for struggle.’

It made me smile.

It’s not the first time a man like me has been called pretty, but it’s the first time it’s been implied that I’m a certain flavour of delicate that denotes and expects softness and care. I’ve always been the carer, not the cared for.

Hands aren’t always kind, lips even less so. Sticks break bones but words stain, they tattoo deep under the skin and nothing, no amount of scrubbing nor insouciance will get them out.

It felt like it ushered in a new dynamic in our throuple, one where they’d lie on either side of me and stroke my face softly, whispering incoherent soothings as I let my eyes bubble over.

When I handed the bruised fruit back to them, back then, the first time we met, my eyes had glazed over. A plummy couple in their 60s – her covering up her greys with a sharp brown bob, cutting her face at the chin. She wore a navy-blue turtleneck – it looked soft even to the eye, probably cashmere. And this denim skirt to the calves, covered up with black leather boots, with a pointy heel. He – in a long-sleeved button-down, with brown check trousers that must be the kind they call slacks. I’ve always wondered what made them slacks – but seeing his, with the seam tented down the middle, I figured this must be them.

What I mean to say is they were innocuous, vacuous, I looked at the both of them, this upstanding couple and saw a hole and filled it with thoughts about slacks, and country houses and friends in high places and voices that whistled through noses. But when they spoke, and he spoke first, he took the tomato from me.

‘Oh, you didn’t have to do that.’

‘I know…just helping.’

He looked at me with a sliver of something in his eyes, ‘helping out the OAPs?’

That’s when I looked at him properly, my tongue already unfurling with apologies, silenced when I recognised the humour in his eyes and smiled too.

They had a son, around my age. But the youthful similarities didn’t put them off. Twenty-something was an age that they missed,that they idolized; it’s when they first met.

And that’s about all I understood of them. I never sought more. What they filled me with was more than enough. Maybe I was selfish.

But they sought to understand me. And perhaps that’s what caught me. When you live rooted in fear, it’s second nature to let people control you. And if they don’t, you might take that blossoming of freedom for love.

‘When did you first fall in love?’ She stroked my cheek whilst asking.

‘I was seventeen. She was beautiful and optimistic.’

‘Just like you.’

‘I guess … But she just saw me as a friend.’

‘Did it go any further?’

It was my first time. I remember the rush of excitement when Marnie came to mine. Her dark brown skin shone bright and shiny – probably Vaseline, because it was the summer and the gyaldem had to keep from being ashy. She was dressed plainly, but it was transcended by her beauty. A pair of denim shorts which cut off just above the knees, a white vest top, the straps of her baby pink bra peeking through, her hair slicked up into an impossibly high ponytail, higher than I’d had reason to believe my life might ever reach, and a pair of bright bronze heart-shaped earrings in her ears, everything about her was shiny.

We’d met at sixth form, kissing our teeth at the back of class when teachers told us our potential, not believing for a second they could know it’s true limit.

‘Guess what?’ She sat by me on the bed.

‘What?’ I’d gleaned by that point that fewer words cultivated an air of mystery, even when my silence was only due to the fear strangling my throat.

‘Ty and I are done.’

‘For real?’

She lightly placed her hand on my thigh in response.

I swallowed a million times before her hand moved further upwards.

Afterwards, I felt like something new. And naivety trumped me asking the question:

‘So you’re my gyal now, right?’

Not even an hour later, as we walked down Brixton high street. The summer night grew a chill and I threw my grey hoody over her shoulders. Seeing her swamped in it, covered up with my things, made me smile so hard my face burst at the seams. And it made me even surer: Of course I didn’t have to ask, she was mine.

Then we saw Ty. His arms around a new girl. Marnie stepped forward, stumbled, didn’t even notice when my hoody crumpled into a heap on the floor behind her.

And despite the beautiful moment we’d shared, she turned into my shoulders to cry, ‘how could he do that to me?’

And that’s how love went for me. So I’d avoided it ever since. Until them.

‘You’ve changed.’ This from my mum, one side of her lip raised. Not quite of her own accord, involuntarily by her disgust or scepticism.

‘What you wearing, man?’

It was a silk shirt, dark burgundy, progressively becoming stained from greasy fingers nabbing the corner and holding it up above my shoulder as if it caused offence.

He’d rubbed my shoulder in that exact same spot when he caught me trying it on, fishing it off the floor of his walk-in wardrobe and placing the cooled fabric against my skin.

‘You should keep it, it looks far better on you than me.’ He’d smiled at us both in the mirror.

People smiled whenever they saw us. The three of us. We had dinner in the Bulgari restaurant in Mayfair. We sat in a booth. Plush grey upholstery that made us sink down, sink in, sink towards each other – me in the middle. I fed him a piece of rare steak, right off my fork. I fed her warm berries, it dribbled over my fingers. Then I heard giggles, and I looked over. A bougie birthday party of eight. The girls laughed whilst simultaneously cutting their eyes at me, throwing their weaves over their shoulders. The men also daggered me with their eyes, muttered things, thinking I should feel shame. Thinking the things they muttered might reach the hole in me, like throwing pennies down a well. But they’d already started to fill me back up, my loves. The well was growing shallow. The pennies barely ring through and echo when they fall now.

When they looked at me maybe they saw a hole and filled it with amusement, kind words, soft touch, looking at me and recognising constriction, limits and good old-fashioned hunger. A space that needs filling and that will need more than one love to do it.

That must be what they saw in my eyes, a hungry heart.

And I, in theirs, a hungry love.

Thank you for reading Between Magazine. You can find out more about our mission to platform work created by BIPOC from marginalized genders here:

If you’d like to submit work please read our submission guide here: